This section includes products such as razors and depilatories. The text below provides some historical context and shows how we can use these products to explore aspects of American history, for example, the links between innovation, advertising, and personal identity. To skip the text and go directly to the objects, CLICK HERE

Personal care products which remove unwanted hair from the face and body were developed to address interwoven concerns about hygiene and personal appearance. Removing body hair helped stave off infestations of lice and other parasites, especially for those who lived in close quarters and who had limited access to bathing. Because hair traps perspiration, it can also become a breeding ground for bacteria and odors. For these reasons, by the early 1900s being “clean-shaven” had become associated with basic hygiene.

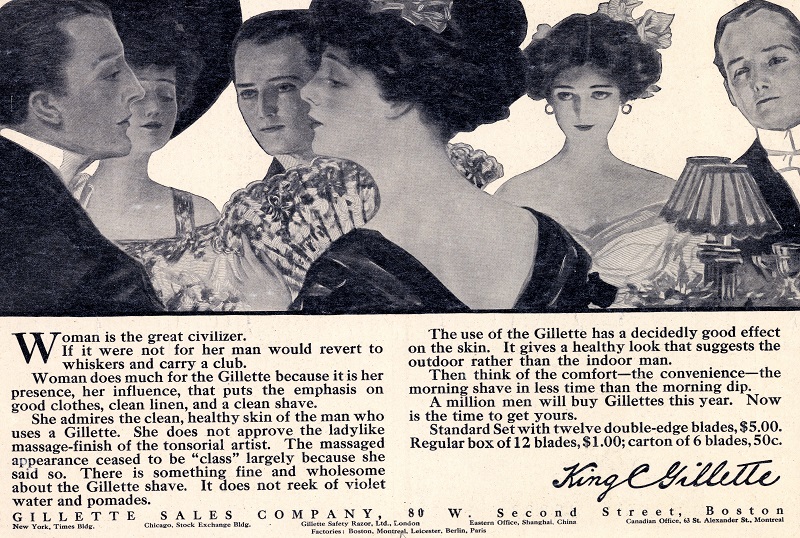

Concerns about personal appearance have often motivated hair removal practices. These same concerns have frequently been used to create and reinforce identity and gender norms within American cultures. Companies have marketed their shaving products in ways that link the use of the product with an increase in the user’s attractiveness, masculinity, or femininity.

Cultural standards, practices, and fashions for men’s facial hair have shifted over time, and razor innovations and marketing have played a role in those shifts. During the 1800s, shaving was done with a steel straight razor, often by a barber. When Gillette patented the first safety razor in 1904, it became easier for men to shave themselves at home. As a result, being clean-shaven became both more convenient and very fashionable.

|  |  |  |

| Steel straight razor | Folding safety razor | Safety razor with replaceable blades | Schermack Round Razor for armpits |

Because personal safety razors use disposable blades, men who shaved every day also had to purchase a constant supply of blades. Marketing for men’s personal shaving products emphasized the idea that the man with a clean-shaven face is a hygienic, modern, and civilized man (in contrast to the man who gets a once-a-week shave at the barber).

|

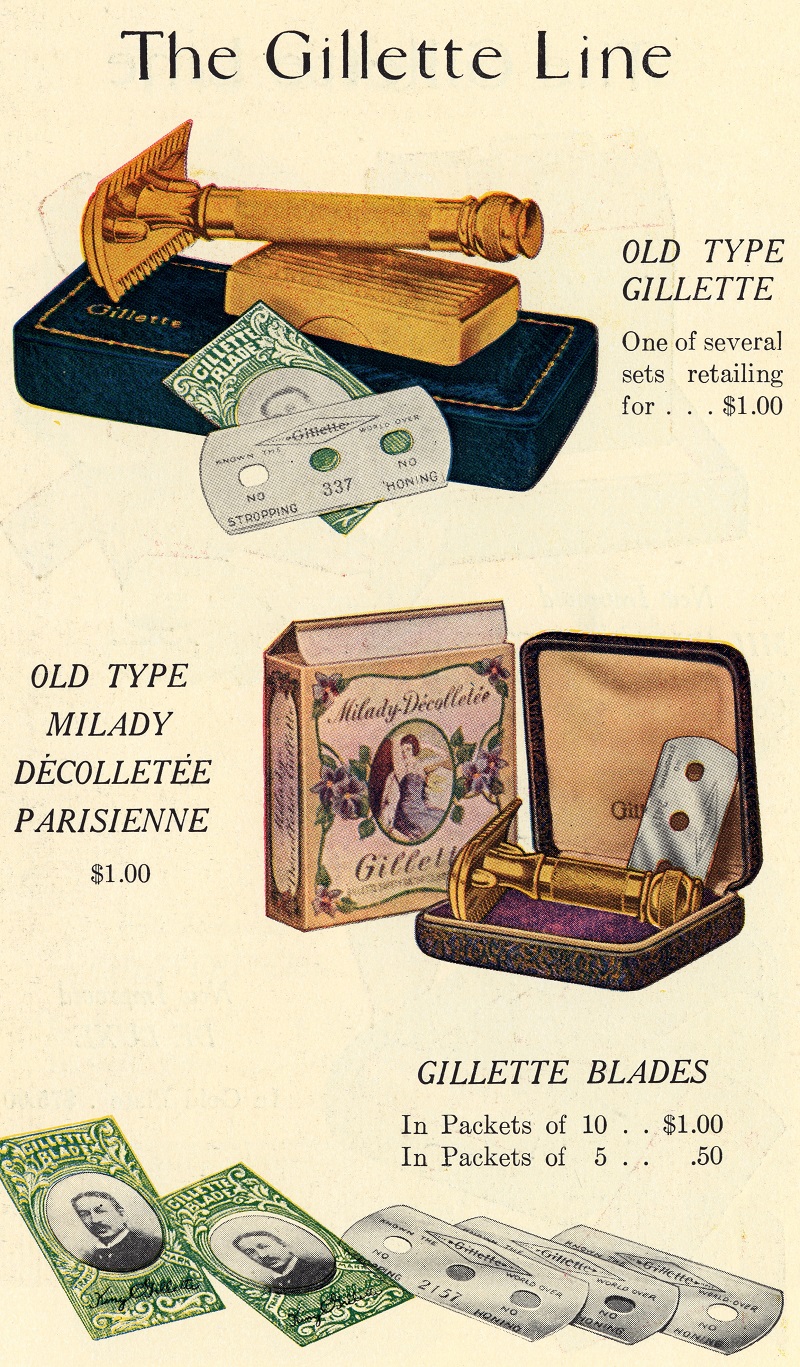

| Gillette Catalog Advertisement for Razor sets. Warshaw Collection of Business Americana, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution |

American beauty standards and practices for women were also affected by the innovation and marketing of the safety razor. Beginning in the early twentieth century, manufacturers of safety razors, seeking to expand their market, promoted the idea that body hair on women is inherently masculine and indelicate, as well as unhygienic. Gillette introduced the first razor marketed specifically to women, called the Milady Decollette, in 1915. In the 1920s, the new fashion for sleeveless tops and short dresses meant that the legs and armpits of American women were now visible in social situations, and advertisers seized the opportunity to encourage women to shave their legs and their armpits.

Because the term “shaving” was associated with masculine facial hair practices, marketers were careful to not use that term in their advertising. Rather, they encouraged women to make their legs and armpits “smooth.” Likewise, razors were not marketed to women for facial hair removal. Instead, women with facial hair were offered products to bleach, wax, or dissolve facial hair.

As different types of razors came into use, other products were manufactured to “partner” with particular razors or particular shaving techniques. Men who shaved themselves also purchased shaving soap, mugs pre-filled with shaving soap, and shaving brushes. Companies continued to develop new razor designs for men and women, which required proprietary blade cartridge refills; these, too, required repeat purchase. Simple shaving soaps gave way to a wide selection of shaving creams and gels, while various talcs, lotions, and aftershave products were developed to sooth the skin post-shave.

Some American consumers sought longer-lasting methods of hair removal, as well as methods that did not risk the cuts and ingrown hairs inherent to the shaving process. Mitts were marketed that, when worn on the hand and rubbed against the legs, scraped off or pulled out the undesired hair. Druggists also sold commercial depilatories, which chemically break down hairs so that they can be wiped away. A 1908 advertisement for X-Bazin’s Depilatory Powder, entitled “Personal Comeliness,” states that the product will remove the “misery attending growths of hair on the face, neck, or arms.” However, depilatory powders and creams often irritated the skin.

Electric razors made hair removal more convenient and less dangerous. Jacob Schick received a patent for the first electric razor in 1930, which he called the “Schick Dry Shaver,” as no shaving soap was necessary.

|  |  |  |

| X- Bazin Depilatory Powder | Coty Ultra Legs Superfoam Hair Remover | Magic Fragrant Cream Shave: Razorless Beard Remover | E-Z Hair Removing Glove |

Bibliography ~ see the Bibliography Section for a full list of the references used in the making if this Object Group. However, the Hair Removal section relied on the following references:

Adams, Russell B. King C. Gillette, the Man and His Wonderful Shaving Device. Boston: Little, Brown, 1978.

Jones, Geoffrey. Beauty Imagined: A History of the Global Beauty Industry. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2010. https://site.ebrary.com/id/10362197.

Peiss, Kathy Lee. Hope in a Jar: The Making of America’s Beauty Culture. New York: Metropolitan Books, 1998.

Sherrow, Victoria. Encyclopedia of Hair: a Cultural History. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2006.