The story behind the color of your couch, and everything else you own

Color surrounds us. Both outside and inside our homes, color is often the first thing we notice.

The natural world is full of color, from plants to vegetables to animals. But what about the products you buy whose color is chosen for them?

Think about the clothes you wear, the couch you sit on, or the car you drive: Each item was assigned a color or colors. Designers handpicked the color of your dishes, your desk lamp and even the bag of chips you ate for lunch. The colors of all these consumer products, and many more, are specifically selected to appeal to us.

Who selects these colors? Corporate colorists and designers are responsible for choosing the right palette for a product or brand. These roles have existed for decades, ever since companies realized the importance of choosing the right, and avoiding the wrong, colors for specific products.

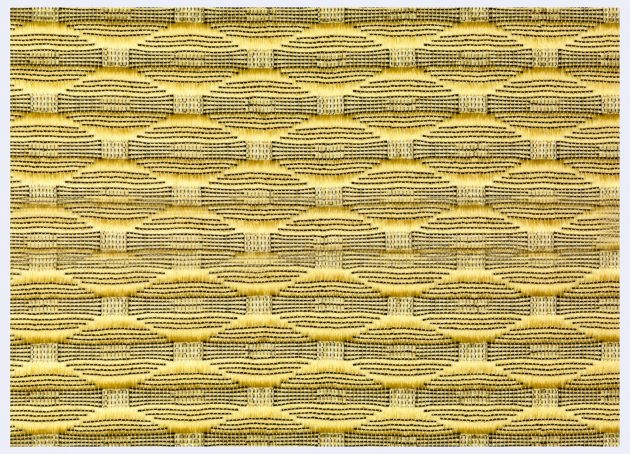

For centuries, designers and manufacturers have produced specialized tools like textile color blankets, sample plates and shade cards to develop palettes and coordinate production.

“The invention of synthetic color in 1856 revolutionized the way color is chosen and marketed for consumer goods,” says Jennifer Cohlman Bracchi, librarian at the Smithsonian Libraries branch at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City. She is co-curator of the museum’s exhibition “Saturated: The Allure and Science of Color.”

“The major increase in the colors available meant there were a lot more opinions about how to choose the right color palette,” Bracchi says. “After World War II, specialists started advising big industries about the colors they should consider for their products.”

Choosing the right color became even more important as industry began to move from custom-made to mass-produced.

“A mistake in the color of a mass-produced product, especially one as costly to produce as an automobile, could be catastrophic for the bottom line,” says Susan Brown, associate curator of textiles at Cooper Hewitt and co-curator of the exhibition.

Selecting the colors of consumer goods is an intricate process, the exhibition illustrates.

Where do designers even begin to look for potential colors and color palettes? Color forecasting books.

“Color forecasting companies, like PeclersParis in France, anticipate color trends by looking to art and culture, as well as socio-economic and political factors. They try to predict where global attitudes are moving and how that is represented in color choice,” Brown says. “Almost every consumer product company consults trend forecasts and relies on color predictions.”

PeclersParis publishes a biannual Colors Trend Book for designers that features photo collages and sample materials. Cooper Hewitt visitors are invited to flip through the Spring/Summer 2018 edition of the Color Trend Book, and to develop personalized color palettes through an interactive, electronic display.

Even when taking color forecasting into consideration, designers still have a lot to choose from.

“In some instances, corporate colorists work with a company’s design team to come up with a color palette that is economically feasible without limiting it too much,” Bracchi explains.

A design team might have 300 colors to choose from when designing a product.

“This isn’t effective because it’s too much to choose from and some colors will inevitably be too similar to each other,” Bracchi says. “Corporate colorists negotiate and compromise with designers to reduce the palette to something more feasible.”

Designers must also consider buyer trends and choosing colors that will appeal to their target consumers. Color can change the perception of a certain product or attract a particular type of customer.

“In 1957, Ford Motor Company launched the Fairlane 500 Club and Town Victoria with the option of a lemon yellow and silver metallic upholstery,” Brown says. “They were trying to appeal to women, who were a growing consumer group for the auto industry after the war. This fashion approach to designing car interiors sometimes even went as far as to offer matching car coats and umbrellas to go with the upholstery.”

Sometimes, it is consumer demand that drives the color selection.

In 1993, Henry Dreyfus Associates reintroduced the Signature Princess Telephone in pale pink, which had originally been produced in the 1960s to appeal to teenage girls. The renewed consumer interest in this retro look drove the manufacturer to once again produce the iconic pink phone.

Corporate colorists work to bring the most appealing colors to the market, and also to develop a recognizable color palette for a brand.

The iMac Computer that Jonathan Ive designed (1999–2000) became the best-selling personal computer in the U.S. with its bright, translucent case available in five colors named for fruits. The blueberry model is on view in the exhibition, but consumers could also pick grape, tangerine, lime or strawberry.

Note: “Saturated: The Allure and Science of Color” was on view at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum through Jan. 13, 2019. The exhibition featured more than 190 objects, and more than three dozen rare books of color theory featuring illustrations—spheres, cones, grids, wheels—that showcased a dazzling spectrum of early efforts to model, systematize and measure color.