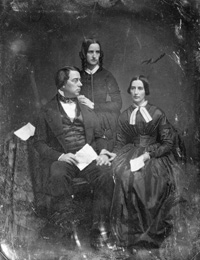

George Perkins Marsh was born in Woodstock, Vermont, in 1801. He served as a Whig representative in Congress from 1843 to 1849. As a congressman he actively participated in the debates and discussions that formed the Smithsonian, and he was a member of the Smithsonian Board of Regents from 1847 to 1849. He received a diplomatic appointment from President Zachary Taylor as U.S. minister to Turkey in 1849, where he remained through 1854. He then returned to Vermont for a few years, and in 1861 President Abraham Lincoln appointed him U.S. minister to Italy, where he served until his death in 1882. During his lifetime he was renowned as a lawyer and linguist, but today he is best known as the guiding spirit of the American environmental movement due to his influential book, Man and Nature; or, Physical Geography as modified by human action, first published in 1864.

|

Marsh was an avid reader from boyhood. He began buying books while a student at Dartmouth College, from which he graduated in 1820. By the late 1830s, when he was practicing law in Burlington, Vermont, he had begun to form a print collection to illustrate the progressive stages in the history of engraving. Although the cultural values that prints represented were acknowledged and shared by many members of antebellum society, Marsh collected prints somewhat earlier—and much more avidly—than most Americans. His natural inclination for study, analysis, and the comparison of proofs, together with his acquisition of European Old Master prints, distinguished him from most American art lovers. Even without many opportunities to see other collections, he managed through his voracious reading to acquire specialist knowledge and to develop strict criteria for judging the quality of impressions.

Most of Marsh’s contemporaries who collected prints did so as a result of foreign travel, but Marsh did not acquire his prints—or even his taste for them—while on the Grand Tour. He did not visit Europe until after he sold the collection to the Smithsonian. His strong scholarly interests in art, languages, and medieval literature led him to patronize East Coast book dealers who specialized in foreign-language titles. Some of these firms imported art books that developed his interest in prints. They supplied Marsh with European catalogs and collectors’ manuals that advised him on which prints to acquire and informed his growing connoisseurship.