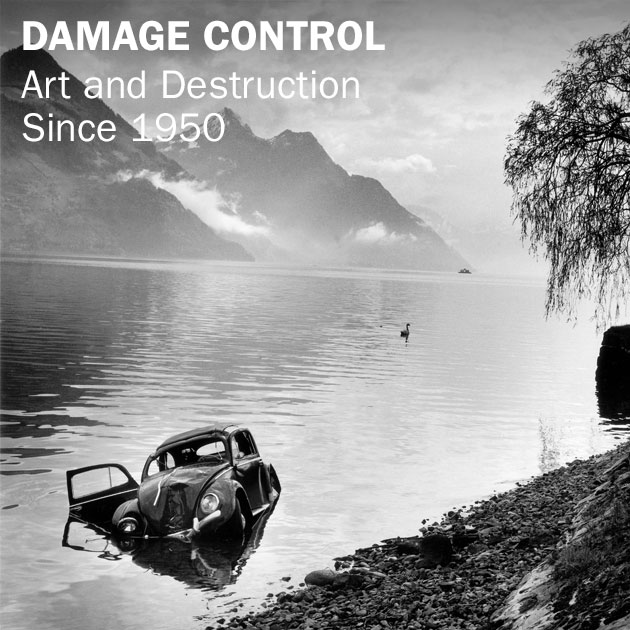

Hirshhorn Presents “Damage Control: Art and Destruction Since 1950”

Destruction has played a wide range of roles in contemporary art—as rebellion or protest, as spectacle and release, or as an essential component of re-creation and restoration. “Damage Control: Art and Destruction Since 1950,” on view at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden through May 26, 2014, offers an overview, if by no means an exhaustive study, of this central element in contemporary culture. Featuring approximately 90 works by more than 40 international artists, and including painting, sculpture, drawing, printmaking, photography, film, video, installation and performance, the exhibition presents many of the myriad ways in which artists have considered and invoked destruction in their process.

“I felt there was a need to create a thematic exhibition dealing with the numerous artists who, since around 1950, have harnessed the powers of destruction as a counterattack on the destructive forces in a world close to the apocalypse,” said Kerry Brougher, Hirshhorn interim director and chief curator. Co-curator Russell Ferguson, professor of art at UCLA, stated that at the same time he “had become interested in exploring the way artists, from the mid-60s on, had begun to re-engage with destruction as a vehicle for self-expression, iconoclasm and rebellion. It seemed very complementary to the interests that Kerry had in the theme.” Having previously collaborated on “Open City: Street Photographs Since 1950,” which appeared at the Hirshhorn in 2002, Brougher and Ferguson joined forces again.

In the immediate postwar period, to invoke destruction in art was to evoke the war itself: the awful devastation of battle, the firebombing of entire cities, the dropping of the atomic bomb on Japan and, of course, the Holocaust. Art seemed powerless in the face of that terrible history. Well into the 1950s, the memory of the Holocaust and the ongoing threat of nuclear war cast a shadow over all forms of cultural production. It was particularly during this postwar period, however, that artists began to touch once again on the destructive impulse in art and the theme of destruction in art took on a new energy and meaning.

In the 1950s, as the arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union escalated, the prospect of nuclear annihilation passed from the realm of speculative fiction into the arenas of science and policy, and the theme of global destruction, already paramount to a generation that had seen two world wars in the course of 30 years, became even more immediate. It is perhaps unsurprising, therefore, that many works from the dawn of the nuclear era are documentary in nature. In the 1950s Harold Edgerton, along with his colleagues Kenneth Germeshausen and Herbert Grier, produced the film “Photography of Nuclear Detonations,” which captured a number of test explosions at the behest of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission in ways that revealed their terrifying potential as well as an almost sublime beauty. In Japan, photographer Shomei Tomatsu was commissioned in 1960 by the Japan Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs to record the aftermath of the 1945 blasts. His resulting images of everything from a wristwatch stopped at the moment of the Nagasaki blast to a melted bottle would become the basis of his contribution to his and Ken Domon’s book Hiroshima-Nagasaki Document 1961. Other artists used documentation as a starting point for broader commentary. Bruce Conner, for example, cut up and reassembled found film from many sources to create the extraordinary montage sequences of “A MOVIE” (1958). These culminated in views of the 1946 Operation Crossroads atomic tests at Bikini Atoll, footage Conner would return to in 1976 for his film “CROSSROADS.”

Artists like Gustav Metzger, whose parents died in a concentration camp, Yoko Ono and Raphael Montañez Ortiz took more conceptual or symbolic approaches to respond to the potential for destruction in the world. Metzger’s performances in which he “painted” with hydrochloric acid, Ono’s “Cut Piece” (1965), in which the artist invited the audience to snip off her clothing with shears, and Ortiz’s smashing of pianos or burning of furniture turned destruction into a central means of artistic construction. And Metzger’s manifestos on “auto-destructive art” paved the way for the influential Destruction in Art Symposium, co-organized by the artist and held in London in Sept. 1966, in which both Ono and Ortiz participated.

In the 1960s, artists also addressed themselves to destruction as a phenomenon filtered and represented by mass media. Among the most famous examples are the paintings in Andy Warhol’s “Death and Disaster” series, including those titled “5 Deaths” (1963), in which he used as source material a wire-service photograph of the scene of a car crash. For others, such as Vija Celmins, magazine and television images served as the basis for their work, in her case meticulously rendered images of airplane disasters and automobile wreckage, as well as atomic bomb blasts and the devastation they caused. Jean Tinguely adapted the happenings he had organized around his “self-constructing and self-destroying” kinetic sculptures, which he considered akin to the human machine, specifically to the medium of television. In fact, the documentary Study for an End of the World No. 2 was taped by NBC and broadcast on David Brinkley’s Journal.

This focus on mediation and manipulation of media has continued as a constant through the decades. Included in the exhibition are examples ranging from Johan Grimonprez’s “Dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y” (1997), with its montage of footage of terrorist incidents, and Roy Arden’s “Supernatural” (2005), which presents edited broadcast scenes of a riot sparked by a 1994 loss by the Vancouver Canucks, to the monumental JPEG photographs Thomas Ruff adapted from Internet images, often of scenes of war.

Others have powerfully filtered news events in politically loaded, emotionally wrenching moving-image works. Christian Marclay’s “Guitar Drag” (2000), for example, which presents the destruction of a Fender Stratocaster—plugged in, amplified and howling as it is pulled down the road—offers an evocative, even disturbing response to the latter-day lynching of James Byrd Jr., who was chained behind a pickup truck by white supremacists and dragged to his death in 1998. And in an uncomfortable blend of plausible fiction and incomprehensible reality, Laurel Nakadate’s “Greater New York” (2005) shows the artist posing in Girl Scout regalia on 9/11 as plumes of smoke rise from the Twin Towers in the background, part of her piece suggesting the loss of innocence.

For many artists, destruction becomes a central means of expanding and challenging the very meaning of art itself. Artists have both honored and repudiated the past by attacking the art of earlier generations. Perhaps the most famous example of this is Robert Rauschenberg’s “Erased de Kooning Drawing” (1953), created when the young upstart asked the established abstract expressionist for an artwork he could unmake. When Jake and Dinos Chapman bought and then “improved” an 80-part portfolio of Francisco de Goya’s “Disasters of War” etchings with such additions as grotesquely cartoonish insect heads, the backlash was substantial—the damage of an established cultural treasure (albeit an editioned one) was not only permanent but unauthorized. Yoshitomo Nara’s “In the floating world” (1999) concerns itself with merely symbolic acts of artistic vandalism. For his suite of altered Ukiyo-e prints, the artist damaged nothing but the cultural memory of works by masters such as Kitagawa Utamaro. Nara’s prints are color photocopies of altered reproductions, not originals.

One of the most noted and extreme examples of the destruction of art itself is John Baldessari’s cremation of his own works, a project in which he burned 13 years’ worth of “boring art” he had made. The institutions that house artists’ works are equally susceptible to such attacks, as when Ed Ruscha painted his monumental widescreen-format “The Los Angeles County Museum on Fire” (1965–68), depicting the then-new museum complex on the verge of being engulfed in flames. David Ireland’s “Study for Hirshhorn ‘Works’ (Nighttime, Washington, DC)” (1990) offers a vision of a ring of fire blazing in the evening sky atop the cylindrical museum building, a proposal for a site-specific installation that proved impracticable.

Destruction as rebellion against the very institutions that organize daily living, or as protest against their violation, is another recurrent motif seen in the work of artists who address the notion of home and domestic spaces. Sam Durant violated mid-century modernist ideals in a series of models of Case Study Houses—flimsily constructed and pointedly defaced travesties of domestic utopias. Humbler domestic architecture is viewed in the wake of natural disaster in Monica Bonvicini’s series of post-Katrina paintings, which return to the millennial ideas that no one is ever truly safe and that the apocalypse is fully scalable, encompassing all of creation or one family’s place of refuge. Dara Friedman’s “Total” (1997), in which the artist films herself wrecking a room and then rewinds the footage so that the room is put back together, pairs the ideas of destruction and construction.

Whether as a means of documentation, of protest, of reconstruction or of creative expression, the artistic employment of destruction has served as an essential means of considering and commenting on a host of the most pressing artistic, cultural, and social issues of the past 65 years.

“Damage Control: Art and Destruction Since 1950” is organized by the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., in association with Mudam Luxembourg and Universalmuseum Joanneum/Kunsthaus Graz. The exhibition received major funding from the Terra Foundation for American Art and is also made possible through support from Kathryn Gleason and Timothy Ring; John and Mary Pappajohn; Melva Bucksbaum and Ray Learsy; John and Sue Wieland; Lewis and Barbara Shrensky; Marian Goodman Gallery Inc.; Peggy and Ralph Burnet; the Swiss Arts Council Pro Helvetia; Dani and Mirella Levinas; Barbara and Aaron Levine; the Broad Art Foundation; the Japan Foundation; David Zwirner, New York/London; the Embassy of Switzerland; and Home Front Communications.

The exhibition travels to Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, Mudam in Luxembourg, July 5–Oct. 12, 2014, and to Kunsthaus Graz in Austria, Nov. 15, 2014–March 15, 2015.

Related Publication

To accompany the exhibition, the Hirshhorn and DelMonico Books/Prestel will publish a full-color catalog, including essays by Brougher, Ferguson and art historian Dario Gamboni, author of The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution.

Related Programs

The Hirshhorn offers a range of interactive educational experiences designed to engage people of all interest levels in contemporary art. On Thursday, Nov. 7, at 6:30 p.m., the “Damage Control” galleries will be open in preparation for a curator-led tour of the exhibition at 7 p.m. At 8 p.m., the Otolith Group’s 2012 film “The Radiant” screens in the Ring Auditorium. A response to the partial meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi power plant after the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami of 2011, this experimental documentary examines the history of nuclear energy in Japan.

The ongoing Meet the Artist series brings a diverse group of artists to the museum to discuss their work. In an event co-sponsored by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Yoshitomo Nara, best known for edgy, deceptively cute Neo-Pop paintings of children and animals that draw on Japanese popular culture, will discuss his work Thursday, Nov. 14, at 7 p.m. in the Ring Auditorium. Jake Chapman addresses the theme of destruction that runs through his and his brother’s often violent and controversial paintings, sculpture and drawings Wednesday, Dec. 11, at 7 p.m. in the Ring Auditorium.

For “In Conversation: Marin Alsop and Kerry Brougher” Saturday, Nov. 16, at 6:15 p.m. at the Music Center at Strathmore, 5301 Tuckerman Lane, North Bethesda, Md., Baltimore Symphony Orchestra music director Alsop joins Brougher to discuss themes of destruction, catharsis and renewal. Alsop conducts a performance of Benjamin Britten’s “War Requiem” following the talk. See hirshhorn.si.edu and strathmore.org for details.

On Sunday, March 16, 2014, at a time to be determined, a daylong screening of moving-image works takes place in the Ring Auditorium. Works include Conner’s “CROSSROADS” (1976), Cyprien Gaillard’s “Pruitt-Igoe Falls” (2009), Grimonprez’s “Dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y” (1997), SUPERFLEX’s “Burning Car” (2008), Ant Farm’s “Media Burn” (1975), Christian Jankowski’s “16mm Mystery” (2004) and Doug Aitken’s “House” (2010). See hirshhorn.si.edu for details.

Artists, scholars and other experts address “Damage Control” in depth in several Friday Gallery Talks; visit hirshhorn.si.edu for a complete schedule. The museum’s library of podcasts, archived on its website, makes gallery walk-throughs and interviews with artists accessible internationally.

About the Hirshhorn

The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, the Smithsonian’s museum of international modern and contemporary art, has nearly 12,000 paintings, sculptures, photographs,

mixed-media installations, works on paper and new media works in its collection. The Hirshhorn presents diverse exhibitions and offers an array of public programs that explore modern and contemporary art. Located at Independence Avenue and Seventh Street S.W., the museum is open daily from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. (closed Dec. 25). Admission to the galleries and special programs is free. For more information about exhibitions and events, visit hirshhorn.si.edu. Follow the Hirshhorn on Facebook at facebook.com/hirshhorn and on Twitter at twitter.com/hirshhorn, or sign up for the museum’s eBlasts at hirshhorn.si.edu/collection/social-media. To request accessibility services, contact Kristy Maruca at marucak@si.edu or (202) 633-2796, preferably two weeks in advance.

# # #

SI-426-2013