Four times in American history the Smithsonian ignited innovation

Thaddeus Lowe's Balloon Ascent in Washington, D.C. on May 31, 1862. The Union Army ultimately brought Lowe onboard to establish a balloon corps. Image: Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 95, Box 54, Folder: 9D

As America approaches its 250th birthday in 2026, the Smithsonian is starting to look back into its archives to rediscover and celebrate the Institution’s role in American history. Since 1846, the Smithsonian has not only contributed to major discoveries and conservation successes, but has also offered critical support to some of America’s most prestigious scientific innovators.

Ballooning Innovations During the Civil War

America’s 16th president, Abraham Lincoln, was a fan of technology. He was the first president to embrace the telegraph, using it as his primary outlet for dispersing messages from the White House. He was an early supporter of railroads, even defending them in court. He also brought on Joseph Henry, the first Secretary of the Smithsonian and the preeminent American physicist of his time, as his primary science adviser.

During the Civil War, both the Union and the Confederacy were looking to gain an advantage over the enemy. At the time, balloonist Thaddeus Lowe was testing whether his hot air balloon could be used to see Confederate troop movements from miles away. His friend Henry wrote several letters to the Secretary of War and to the White House sharing Lowe’s successes in controlling his balloon in the air and urging them to hire Lowe. The Union Army ultimately brought Lowe onboard to establish a balloon corps.

Henry also suggested that the military establish the Permanent Commission of the Navy Department, a three-member group that met in the Smithsonian Castle and reviewed proposals from inventors seeking to sell their military technology to the U.S. Government to aid the war effort. The commission ultimately rejected most of the proposals, arguing that they would not be of much use to the Union. The Civil War was not easy on the Smithsonian, whose headquarters sat squarely in between the White House and the Capitol building. Henry handled the budget issues the war caused and even sent a memo asking employees to save paper so that it might be re-sold. Henry’s reputation would be stained, however, when he refused to let Frederick Douglass speak as part of a lecture series promoting abolitionism taking place at the Castle during the war.

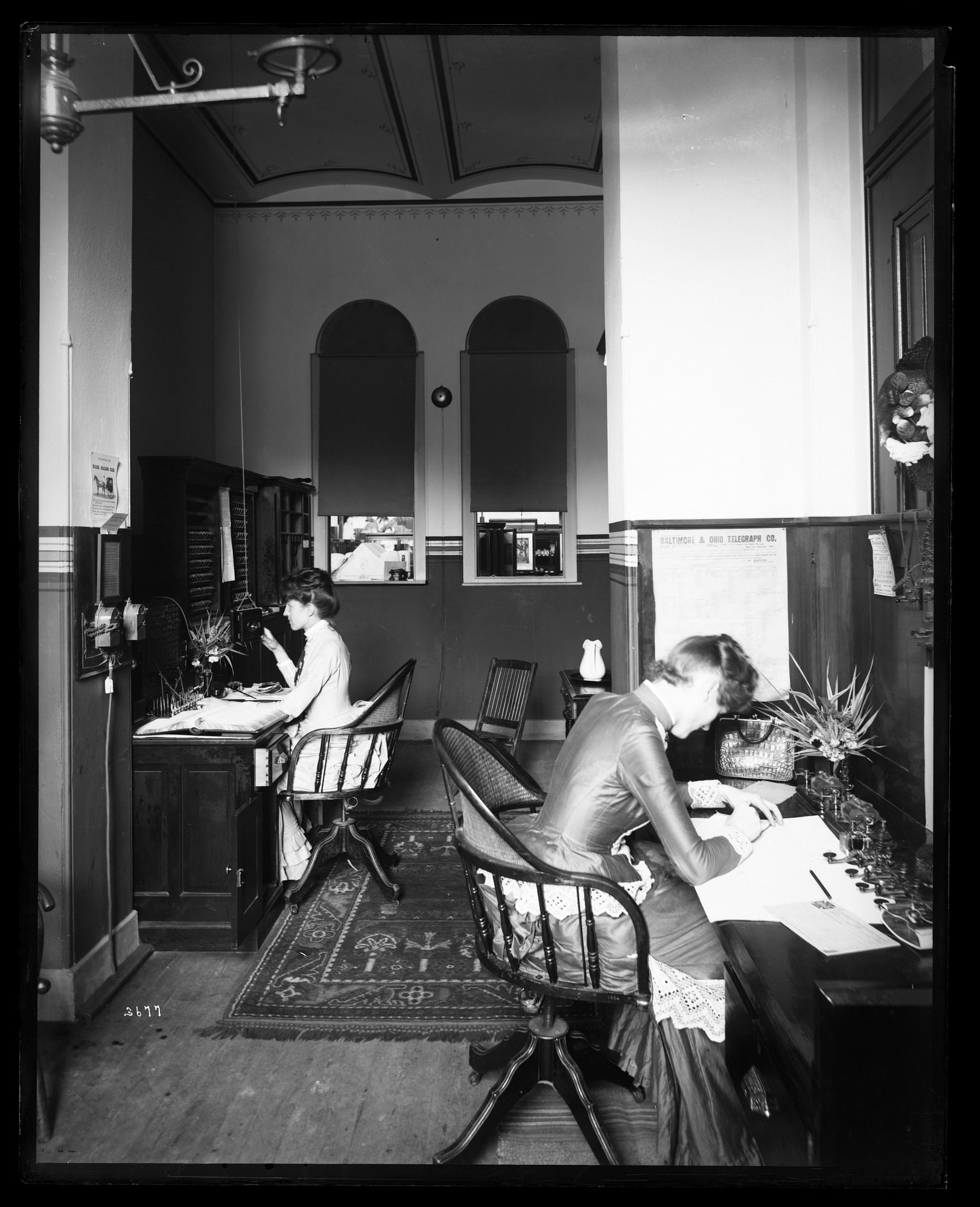

Moving Sound Transmission Forward

Alexander Graham Bell was born in 1847, less than a year after the founding of the Smithsonian, but by 1875, he was already studying the idea of transmitting the human voice through the telegraph. Seeking advice, he turned to Henry, who was still Secretary of the Smithsonian but nearing the end of his life. Henry assured Bell that he had made an original discovery and that his ideas were sound, and he encouraged him to continue his work. A year later, Bell was awarded the first U.S. patent for the telephone. Two years after that, in 1878, the Smithsonian became an early adopter of the telephone, installing a system of electronic bells and telephones in the Castle at a time when the number of phone lines in Washington, D.C., only numbered 187.

Later, Bell served on the Smithsonian’s Board of Regents, where he was put in charge of locating and retrieving James Smithson’s remains. It is “the proper thing to do,” he said, and after a rather treacherous journey to Genoa, Italy, he came back with the remains of the Smithsonian's founding benefactor, which now reside eternally in the Smithsonian Castle.

An Aeronautics Education

In the late 1890s, self-taught engineers Orville and Wilbur Wright were studying the possibility of human flight and they sought the advice of an elder in the field: Smithsonian Secretary Samuel Langley. In a letter dated May 30, 1899, Wilbur wrote to Langley, asking him for a reading list on aeronautics and related topics. At that time, Langley had done extensive aeronautical research and was working on building the first flying machine but was thus far unsuccessful. Langley assisted them, but as they exchanged letters, collaboration turned to competition when the Wrights realized they and Langley were seeking to achieve the same goal. Langley was devastated when the young Wright Brothers surpassed him and launched the first successful human flight at Kitty Hawk in 1903.

The feud reached a fever pitch when Langley’s successor at the Smithsonian, Charles Walcott, had Langley’s flyer restored by a rival of the Wrights and displayed in what is now the Arts and Industries Building, which stands next to the Castle, but was then the National Museum. The placard called it the first airplane, and this did not go over well with the Wrights. Angry at the Smithsonian, the brothers eventually donated their plane to a museum in the U.K.

The Smithsonian formally apologized to the Wrights in 1942, saying that if the family was to bring their plane to the Smithsonian, it would be given “the highest place of honor which it is due.” A year later, President Franklin Roosevelt announced to the country that the Wright plane would come back from England.

Today, the Wright Flyer is the centerpiece of the new, permanent The Wright Brothers & The Invention of the Aerial Age exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

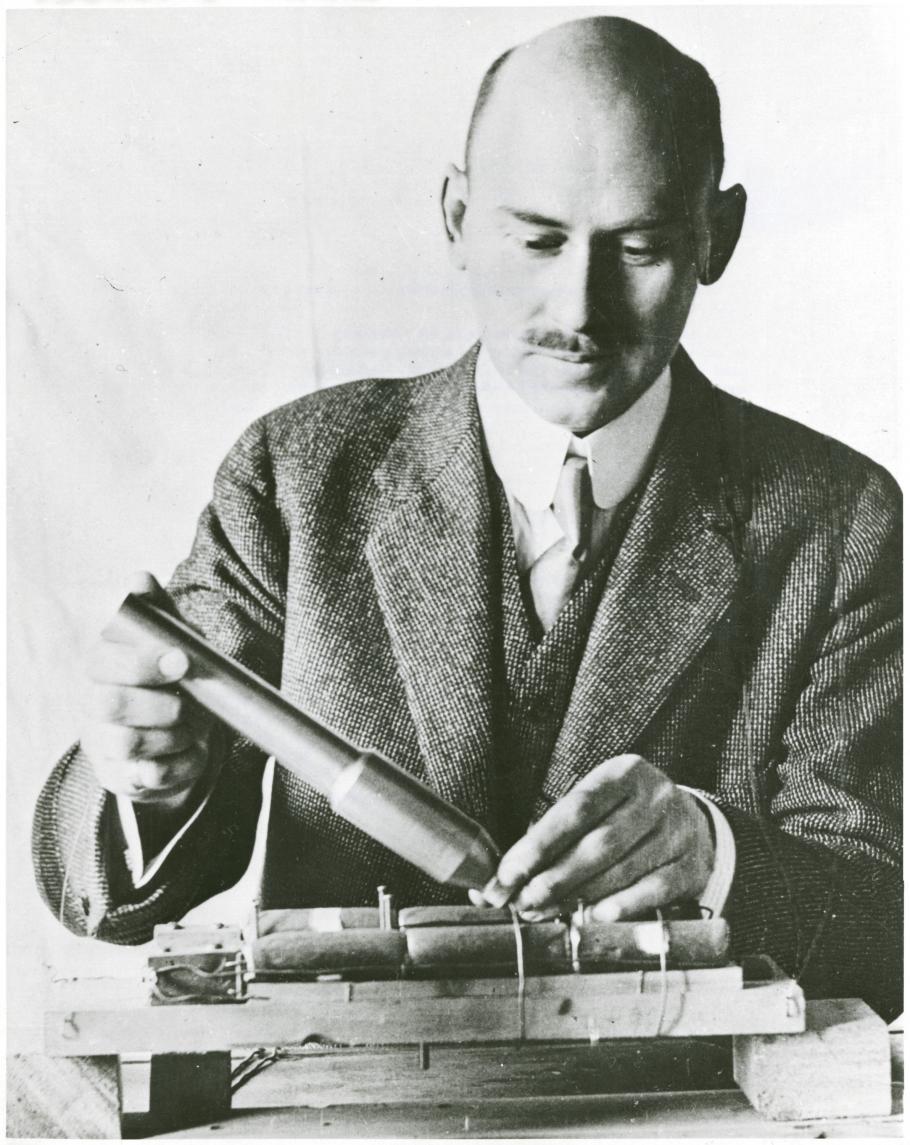

Rocketing Into the Future

In 1916, an unknown professor from Clark College wrote a letter to the Smithsonian where he described his experiments with rockets and requested funds so he could continue his work. After reading the letter, Assistant Smithsonian Secretary Charles Abbot, an astrophysicist, praised the professor’s work as “sound and ingenious,” and he recommended to Secretary Walcott that the Smithsonian support his work. The following year, the Smithsonian awarded this professor—Robert H. Goddard—with a $5,000 grant (the equivalent of $123,000 today).

The Smithsonian published Goddard’s 1919 paper, “A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes,” now considered one of the fundamental works in theoretical rocketry. In the following decades, Goddard established himself as the father of rocketry. On March 16, 1926, he successfully launched the world's first flight of a liquid-propelled rocket, and he is credited with 214 patents, with 131 filed after his death in 1945.

Goddard always credited the Smithsonian for giving him the support he needed early in his career. In a letter dated May 28, 1930, Goddard wrote to Abbot stating that he was "particularly grateful for your interest, encouragement, and far-sightedness. I feel that I cannot overestimate the value of your backing, at times when hardly anyone else in the world could see anything of importance in the undertaking."