Pyrotechnics, pageantry and the ‘virgin vote’: How 19th-century youth shaped democracy

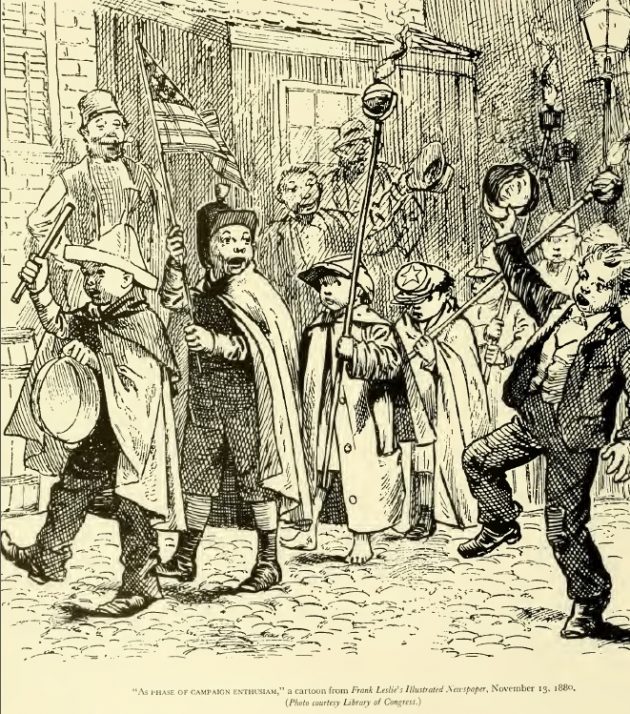

Adults encourage some very partisan children to don uniforms, light torches, and march through their community before the big 1880 election. “A Phase of Campaign Enthusiasm,” Frank Leslies Illustrated Newspaper, November 12, 1880.

Politicians campaigning for the youth vote isn’t anything new.

While the desire to involve young people in the political process stretches back centuries, the tactics—from bonfires to free booze to capes (yes, capes)—have evolved over the years.

“Then and now, youth politics is so much bigger than just voting,” says Jon Grinspan, curator and Jefferson Fellow at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Grinspan’s research focuses on youth in politics in the 19th and early 20th centuries. From his office in the Political History Division of the museum, he points to primary sources like diary entries and newspaper engravings that give us a glimpse into the past.

Democracy hasn’t changed, Grinspan says, but the way it functioned in those eras would surprise American voters today.

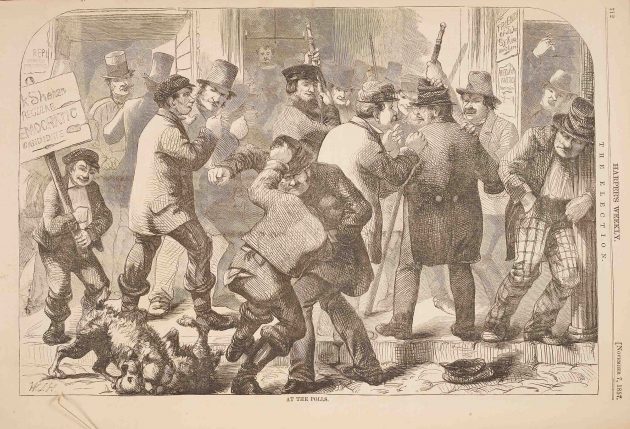

Political involvement might begin at birth, when parents named their children after prominent politicians. Or, youngsters would join their fathers in saloons for late-night discussion of politics. Children were even known to throw rocks at children whose families belonged to an opposing political party.

By the time they were teenagers, boy orators would be giving speeches on behalf of candidates.

Everything led up to a young man’s 21st birthday, when he cast what was commonly referred to as his “virgin vote.” It was seen as a rite of manhood—and more importantly for campaigners, it was an unspoken pledge to remain monogamous to this chosen party for the rest of his life.

Candidates might come and go but party loyalty was forever, and when it was sealed as young as age 21, adults had a good reason for pushing to ingrain devotion from an early age.

Young women weren’t excluded from the political process just because they were barred from voting, according to the Smithsonian’s Grinspan. They had influence over the male voters and policy-makers in their families, and when it came time for courtship, they might turn down a young man from the “wrong party.”

But how do you get a 12-year-old interested in politics? Well, fire doesn’t hurt.

Imagine the spectacle: thousands of people marching down the street for a cause, the women dressed as goddesses, the young men in uniforms, including capes—one of which is now in the American History Museum’s collection. Alcohol flowed freely. And fires raged, as did the spirit of democracy in small rural towns, for whom this was “the Super Bowl and the Oscars and everything pop culture has to offer,” Grinspan says.

Issues weren’t always at the forefront of these events, he adds. In fact, some participants might get the issues totally wrong (!), but they knew what party they were there to support.

“Often being excited about politics stands in for understanding the issue,” Grinspan says.

That excitement led to high voter turnout, unrivaled since the turn of the 20th century.

Flash forward to the 1970s. Adults are still trying to get youth interested in politics, but now with ‘groovy’ outfits that to the contemporary historian look like a desperate appeal to seem hip. While bell-bottom pants might have been in fashion then, emblazoning them with red, white and blue stripes was not the way to a teenager’s heart—or a motivator toward the voting booth.

Youth involvement in politics had tanked, and those outfits – from tank tops to Keds, all plastered with “VOTE” – also made their way into our National Museum of American History collections.

What went wrong? Or, what’s the difference between a cape and a pair of Keds?

“The more adults try to engineer young people’s politics…the less well it works,” Grinspan observes.

Even when adults in the 19th century were suspicious of youth, they knew they needed the young support so they treated adolescents as peers.

At one time, a 15-year-old who was interested in politics would be welcomed into a club with adults. Around 1900, leaders began to separate youngsters into their own youth clubs, apart from the grown-ups.

They had been put at the political kids’ table.

The idea of maturity mattered more than campaigners accounted for, Grinspan says, and when youth were put into a separate (less respected) class, their interest decreased.

Grinspan also notes the difference between being one of a hundred boys marching down the street in matching capes bolstered by the thunderous applause of an entire town, to being one person who shows up at school in patriotic pants.

One of those is empowering; the other is isolating.

And that social aspect of democracy is one thing that hasn’t gone away. We spend just a relative sliver of time voting compared to the time we spend reading, watching or talking about politics, often with those around us.

Democracy functions best when it exists in a community that cares about voting—no matter what they’re wearing, Grinspan concludes.