Marsha Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and the history of Pride Month

Photographic slide of Pride flag banner at a New York City Pride march in the 1980s. Collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, gift of Ron Simmons. Copyright Ron Simmons.

The first Pride parades marked the anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, when police raided the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street in New York City after midnight on June 28, 1969.

That night, after growing tension, police stormed the gay bar and arrested multiple people. Patrons resisted. Riots broke out between patrons and police. The uprising lasted six days.

"For me the reason to remember the Stonewall uprising is in recognition of the daily acts of courage the rioters took that got them to the bar that night," wrote Katherine Ott, curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. For the 50th anniversary of the uprising in 2019, she reflected on its role in the broader scope of LGBTQ+ history.

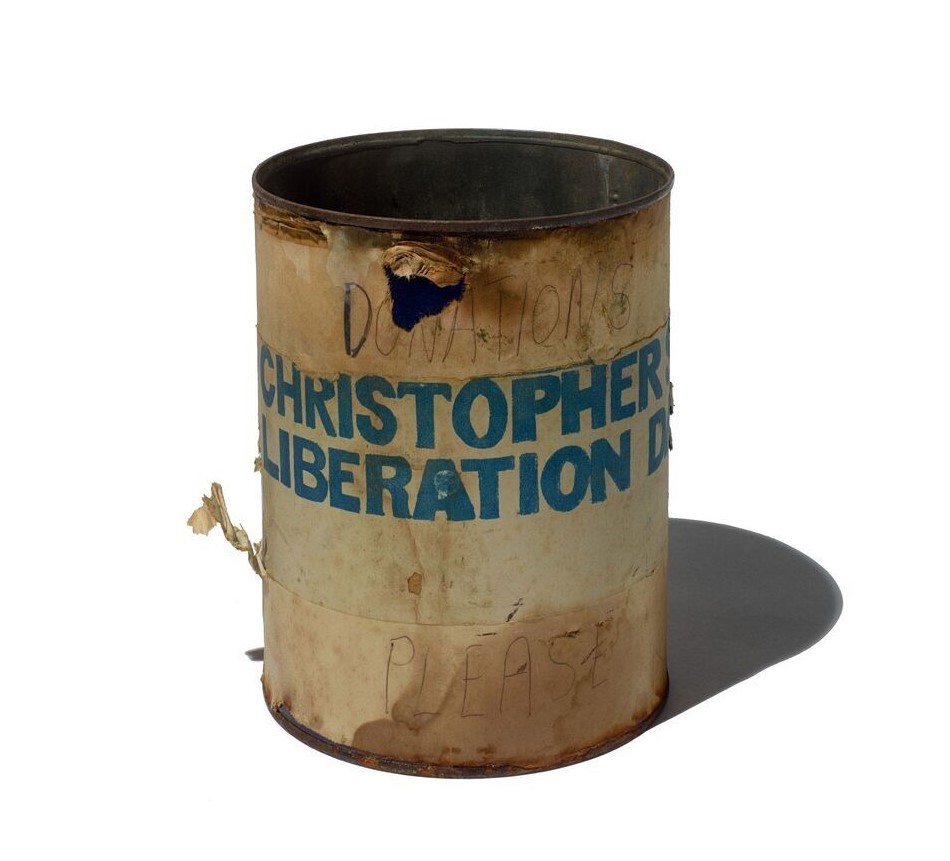

Stonewall was solidified as a key moment in the LGBTQ+ civil rights movement by the marches that began a year later. In New York City, the Christopher Street Liberation Day March is considered the city’s first Pride parade. Today, June is celebrated as LGBTQ+ Pride Month in commemoration of the event.

Marsha P. Johnson, a self-identified drag queen and a prominent gay liberation activist, is one of the most well-known participants in the Stonewall uprising. After Stonewall, her activism continued—she joined the Gay Liberation Front, ACT UP, and cofounded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) with Sylvia Rivera. (Johnson also referred to herself as a “transvestite,” and never used “transgender” to describe her gender identity, since the term was popularized after her death in 1992.)

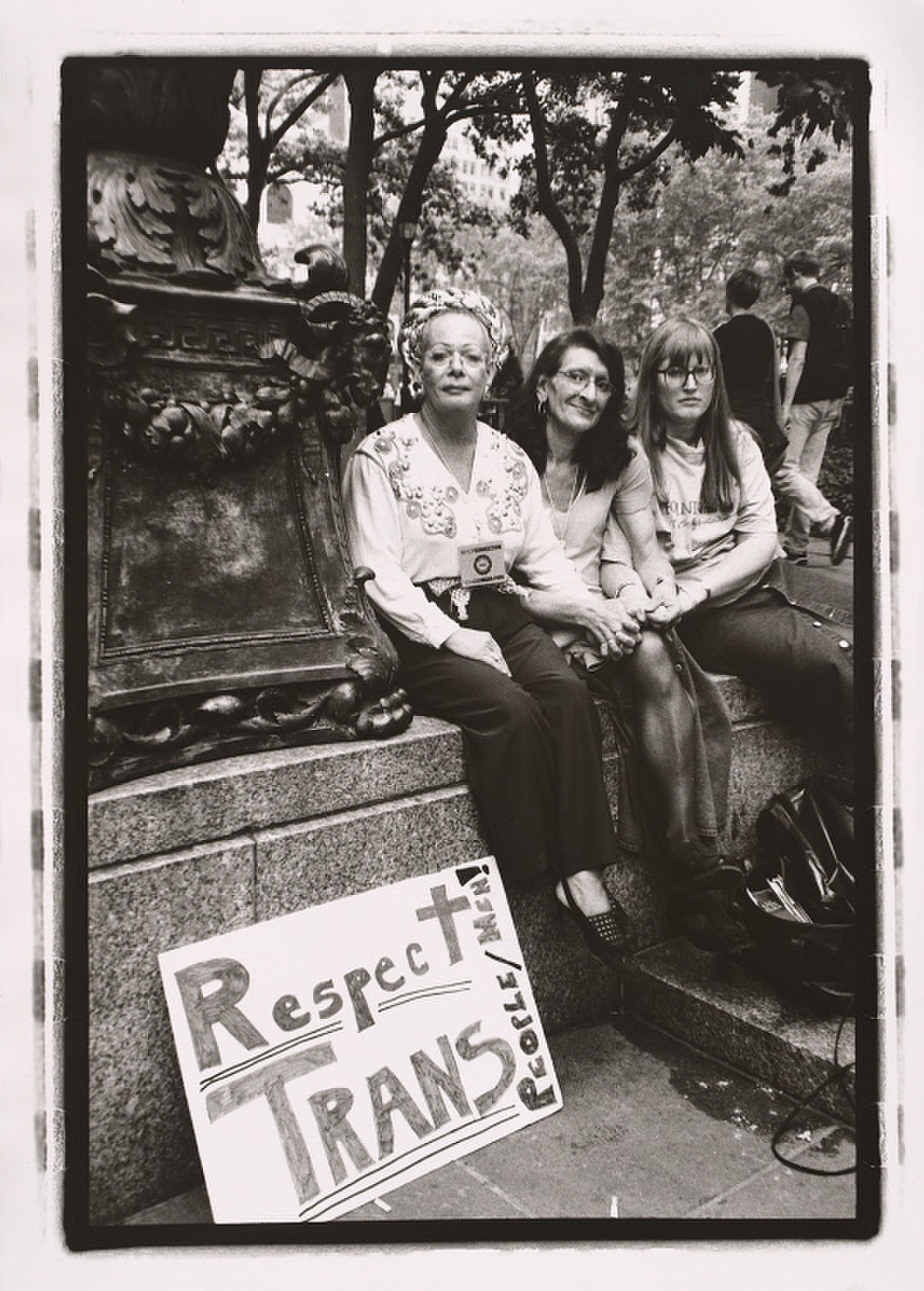

Rivera was also involved in Stonewall, and the experience led her to campaign with the Gay Activist Alliance (GAA) for a city nondiscrimination law. But Rivera, who was a transgender woman and Latina, faced discrimination from established gay rights organizations like the GAA that were predominantly led by white men. The GAA's leadership often rejected the role transgender people—many of them people of color—played in Stonewall.

Together, Rivera and Johnson started STAR House for LGBTQ+ youth experiencing homelessness, with a focus on supporting people of color.

In 1973, when the New York City Pride march organizers banned drag queens (including Johnson) from participating, she and Rivera marched ahead of the parade.

Explore more Pride photos from the Ron Simmons Photography Collection in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, which includes several hundred color slides, most related to U.S. politics, literature, and LGBTQ+ activism.