W. John Kress is director of the Consortium for Understanding and Sustaining a Biodiverse Planet, one of the four grand challenges of the Smithsonian’s strategic plan.

Smithsonian Scientist Proves Pollinators Are More Than Just “Ornaments of Life”

National Museum of Natural History botanist W. John Kress recently co-authored and published The Ornaments of Life, an unprecedented scientific work that synthesizes ecology and evolutionary research from more than 2,000 sources. Inspiration for the book’s title came from Robert Whittaker, an ecologist who believed pollinators to be merely “…evolution’s ornaments of the tree of community function.” In their book, Kress and co-author Theodore Fleming assert that the role of flower pollinators and seed dispersers on the planet’s health is much more than just ornamental, and that the value of these species transcends the beauty found in colorful feathers, fur, flowers and fruits. Vertebrate frugivores and pollinators sustain thousands of acres of tropical forests, which act as carbon sinks and help mitigate the impacts of climate change on the Earth. Additionally, scientists are studying complex animal–plant relationships to improve their understanding of the process of evolution.

One aspect of Kress’ research focuses on two species of tropical plants called Heliconia caribaea and H. bihai, and their sole pollinator, the purple-throated carib hummingbird. The dependence of these species on each another for survival is one of the best-documented examples of co-evolution between birds and plants in the tropics.

“The specialized reproductive strategies that we observe between these heliconias and hummingbirds are an example of Darwinian evolution at its best,” said Kress. “Studying this complex pollinator–plant relationship helps us as scientists understand the story of evolution by demonstrating how organisms continue to adapt to their environment, and each other, over time.”

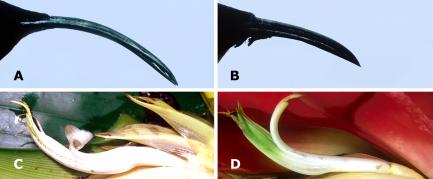

Located in the eastern Caribbean, H. caribea, H. bihai and purple-throated carib hummingbirds have co-evolved to become completely dependent on one another for reproductive success. Male and female hummingbirds each pollinate a separate species of Heliconia flower. The small female hummingbirds, with their long curved bills, have evolved to feed quickly on the long, curved flowers of H. bihai. Conversely, male hummingbirds are larger and have short straight bills to feed on the short, straight flowers of H. caribea. Males defend their flowers from intruding female hummingbirds except during the breeding season, when they allow them to feed on the rich nectar found in H. caribaea in order to mate with them. This example of bird sex-to-flower species co-evolution is rarely observed in nature, but clearly demonstrates a highly specialized inter-species relationship that developed over the course of millions of years.

Heliconias and hummingbirds represent a small fraction of the thousands of species that live in tropical rainforests. These environments are some of the most biodiverse places in the world, and they rely on fruit-and-nectar feeding birds and mammals to pollinate the flowers and disperse the seeds of hundreds of plants. Much of the natural infrastructure of the tropics relies exclusively on pollinators and frugivores, such as toucans, leaf-nosed bats and monkeys. Each of these species fulfills a distinct ecological niche, spreading pollen and seeds that will contribute to the next generation of forests.

As rainforests continue to face pressure from environmental and man-made threats, such as climate change, logging and human development, many species of pollinators and frugivores are becoming endangered. The disappearance of large mammals in tropical forests is particularly troubling, as they are responsible for dispersing large seeds from trees that absorb carbon dioxide from the Earth’s atmosphere. These trees comprise forests that act as one of the planet’s largest carbon sinks, and help reduce the impacts of greenhouse gasses on the planet. Kress and his team hope to study the impact of climate change on additional pollinator–plant relationships to prevent the unsustainable degradation of these forests in the future.

Kress is director of the Consortium for Understanding and Sustaining a Biodiverse Planet, one of the four grand challenges of the Smithsonian’s strategic plan. Kress also serves as curator of botany at the National Museum of Natural History. He is an expert on tropical biology, with interests in the evolution and ecology of tropical plants and animals. In November 2013, Kress received the prestigious Parker/Gentry Award from the Field Museum in honor of his outstanding efforts to preserve the world’s rich natural heritage.

# # #

SI-508-2013