National Museum of African American History and Culture Exhibits Emancipation Proclamation and 13th Amendment

Original copies of the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment are on display in the “Slavery and Freedom” exhibition on Concourse Three of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. The documents share exhibition space with a restored slave cabin used in the early 1800s to house enslaved families on a plantation on Edisto Island, S.C. The Emancipation Proclamation and 13th Amendment are on a long-term loan to the museum by philanthropist David M. Rubenstein, Smithsonian Regent and co-founder and co-executive chairman of The Carlyle Group.

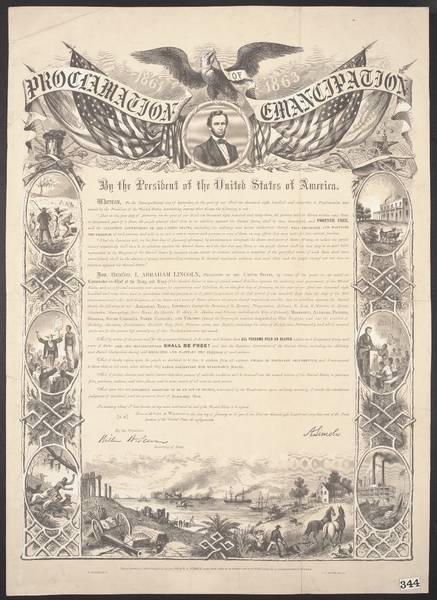

The Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment to the Constitution are among the most important documents in the history of the United States. With the Emancipation Proclamation, issued by President Abraham Lincoln to take effect Jan. 1, 1863, the aim of the Civil War evolved to include the liberation of enslaved African Americans in 10 rebellious states. The 13th Amendment, which passed Dec. 6, 1865, made slavery illegal in the United States.

“These two original documents show a nation in transition: they mark a powerful shift in America’s relation to the millions of enslaved blacks who had been bought and sold and considered property,” said Lonnie G. Bunch III, founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. “Showcasing the documents in the museum helps to illuminate an often overlooked story of how the enslaved, through self-emancipation and other resistance methods, forced the federal government to create policies that led to the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment.”

“Slavery in America often destroyed enslaved families and communities, and yet African Americans survived it with their humanity intact,” Bunch added. “Their stories have shaped the American story and remind us of the enduring power of the human spirit. We are grateful to David Rubenstein—his generosity and his vision—for making these documents available to the museum and to the millions of visitors who will see them. The nation is honored by what he has done.”

Emancipation Proclamation

On Sept. 22, 1862, Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Under his wartime authority as Commander-in-Chief, he ordered that, as of Jan. 1, 1863, all enslaved individuals in all areas still in rebellion against the United States “henceforward shall be free.” African Americans could also enlist in the armed forces. The proclamation was limited in scope but revolutionary in impact. The war to preserve the Union also became a war to end slavery.

Lincoln considered the Emancipation Proclamation to be the crowning achievement of his time in office. “I never, in my life, felt more certain that I was doing right, than I do in signing this paper,” he declared. “If my name ever goes into history it will be for this act, and my whole soul is in it.”

The 13th Amendment

The 13th Amendment completed what free and enslaved African Americans, abolitionists and the Emancipation Proclamation set in motion. On Dec. 6, 1865, the U.S. government abolished slavery by amending the Constitution to state: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

# # #

SI-105-2018

Fleur Paysour

202-633-4761

Melissa Wood

202-297-6161