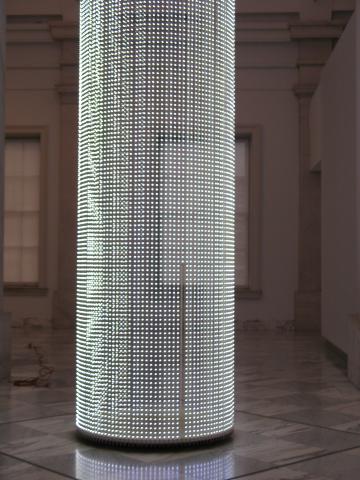

SAAM commissioned Jenny Holzer to build For SAAM for the museum’s Lincoln Gallery and she and her team installed the work in late 2007. It is a 28-foot tall, cylindrical, LED sculpture. An array of 61,200 individually programmable bright white LEDs animates a series of the artist’s texts, revolving the phrases around the structure (fig. 1, below).

After approximately ten years of continuous exhibition, technological issues in the piece led SAAM to have the artwork completely re-fabricated. Brooklyn-based firm Parallel Development rebuilt the piece in 2017 and re-installed For SAAM in January 2018.

Initially there were three types of recurring failures; solder joint failure, LED segment failure, and integrated circuit failure. During that period, replacement of failed components with artist-provided spare parts was an acceptable treatment and maintained the visual aesthetic of the artwork.

In 2014, a new issue surfaced. Replacing LED segments no longer maintained the work’s visual aesthetic. The piece uses phosphor LEDs, which produce white light through the interaction of a blue diode and a yellow phosphor coating. As the LEDs age both elements degrade, and the result is dimming and color shift. After 7 years, the LEDs in the piece had been operating long enough to change significantly. When conservation replaced a malfunctioning segment, the difference in appearance between the new, unused segment and the segments surrounding it was obvious. Patches of brighter, whiter segments were apparent throughout the sculpture.

In 2015, the technical problems had accrued to such an extent that there was significant institutional support for a major conservation project. The museum ultimately decided refabricating the work was the best approach, and after conferring with Holzer’s studio this became the accepted path forward. The main rationales for this approach, versus rehabilitating the piece as it was built, were consistency of presentation, easing maintenance, and the effective use of resources. Maintaining the same technology would likely generate diminishing returns as far as performance, while also guaranteeing the same problems would recur. Both avenues required significant expenditure, so the Smithsonian and the artist favored the path that led to a more stable end result. The artist tied the identity of the work most strongly to the ultimate effect of the piece, which required an even, bright white luminous presentation. This devalued the precise technological components that originally achieved the effect. Newer technology would provide a more consistent presentation, and the redesign would allow the opportunity to obviate some of the maintenance problems the museum routinely faced.

Parallel Development re-designed the hardware to take advantage of advances in LED technology since 2007. While this was an intimidating project, all parties were confident the identity of For SAAM would persist in its second iteration through the collaborative effort. The museum was able to pursue this strategy thanks to generous support from the Smithsonian’s National Collections Program.

The fabrication company Sunrise Systems designed the original iteration of the work. SAAM’s former Curator of Film and Media Arts, Michael Mansfield, produced a block schematic illustrating the signal flows in the piece (fig. 2, below).

An HP OmniBook laptop supplied video data to the piece using a DOS executable. The program generated the animations in real time and transmitted the data to the 12 motherboards housed in the collar of the work. The collar, also referred to as the halo, was the topmost structural element in the work. It attached to a hole in the gallery ceiling, which accommodated the data and power lines.

One can think of the LED array as a large video monitor, with LED diodes playing the role of the pixels. The array is comprised of 120 LED strands, with 510 diodes in each strand. The frame size of the monitor is therefore 120 pixels wide by 510 pixels high. Given restraints on the amount of data that the DOS laptop could transmit, and the speed of that transmission, Sunrise Systems transmitted LED diode instructions one strand at a time.

Each of the 12 motherboards fed data to 10 strands of LED segments. Data traveled linearly across the motherboards. The motherboard in the first position received the first strand of data, and those LED instructions determined which LEDs in the first strand turned on or remained off. When the next strand transmission arrived, the first strand changed according to the new instructions, while the motherboard carried the data from the first strand over to the second strand, and those the lit up accordingly alongside the new configuration in the first strand. The motherboards copied and moved the strand data this way as new instructions arrived, all the way to the 120th and final strand. This is how the piece generated animation effects, one strand at a time, and always moving in one direction.

Data was also distributed linearly down each LED strand – the topmost LED segment in the strand received all the strand data, it then implemented the instructions for its diodes, and sent the rest of the data through to the segment below, which enacted the relevant instructions on its diodes and sent the remaining data down, all the way to the last segment nearest the ground.

Data passed vertically between the LED segments via the solder joints. Therefore, when these joints suffered problems, the segments below ceased to receive any data. The visual signal of this issue was a strand with LEDs either always on or always off below the effected segment (fig. 3). The solder joints provided structural support and data transmission, making them vulnerable to damage.

About the Artist

Jenny Holzer (born July 29, 1950) is an American neo-conceptual artist, based in Hoosick Falls, New York. The main focus of her work is the delivery of words and ideas in public spaces.

Holzer belongs to the feminist branch of a generation of artists that emerged around 1980, looking for new ways to make narrative or commentary an implicit part of visual objects. Her contemporaries include Barbara Kruger, Cindy Sherman, Sarah Charlesworth, and Louise Lawler.

The public dimension is integral to Holzer's work. Her large-scale installations have included advertising billboards, projections on buildings and other architectural structures, and illuminated electronic displays. LED signs have become her most visible medium, although her diverse practice incorporates a wide array of media including street posters, painted signs, stone benches, paintings, photographs, sound, video, projections, the Internet, T-shirts for Willi Smith, and a race car for BMW. Text-based light projections have been central to Holzer's practice since 1996. As of 2010, her LED signs have become more sculptural. Holzer is no longer the author of her texts, and in the ensuing years, she returned to her roots by painting.

[This biography is from Wikipedia under an Attribution-ShareAlike Creative Commons License.]