The year 1968 was turbulent and marked by historic watershed events that resonate today. Take a closer look at a selection of items that reveal the year.

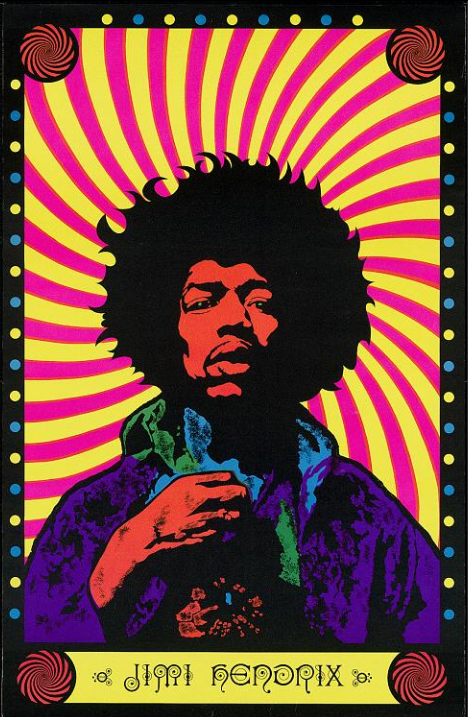

Jimi Hendrix Poster

“Jimi Hendrix” by an unidentified artist. Color photolithographic

poster on paper. Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery

“He changed everything. What don't we owe Jimi Hendrix? For his monumental rebooting of guitar culture ‘standards of tone,’ technique, gear, signal processing, rhythm playing, soloing, stage presence, chord voicings, charisma, fashion, and composition...He is guitar hero number one.”—Guitar Player magazine, May 2012

James Marshall "Jimi" Hendrix bought his first acoustic guitar at 15 and taught himself to play by listening to the music of Elvis Presley, B.B. King and Muddy Waters. His father soon bought him his first electric guitar because he couldn’t be heard above the sounds of his band, the Velvetones. Hendrix served in the army then went to New York City where he was a studio musician and played in back-up bands. He moved to England in 1966 where he formed the Jimi Hendrix Experience. His playing and showmanship created a sensation in Europe, and the Experience’s songs topped the British charts. Hendrix returned to the U.S. where the Experience had a hugely successful tour.

In 1968, he released the band’s album Electric Ladyland, his third studio album; it reached no. 1. Despite the group’s success, it disbanded in 1969. Hendrix played at Woodstock that summer, where he formed another band that evolved into the Band of Gypsys.

Hendrix was the world's highest-paid rock musician by 1969. He died Sept. 18, 1970, in London.

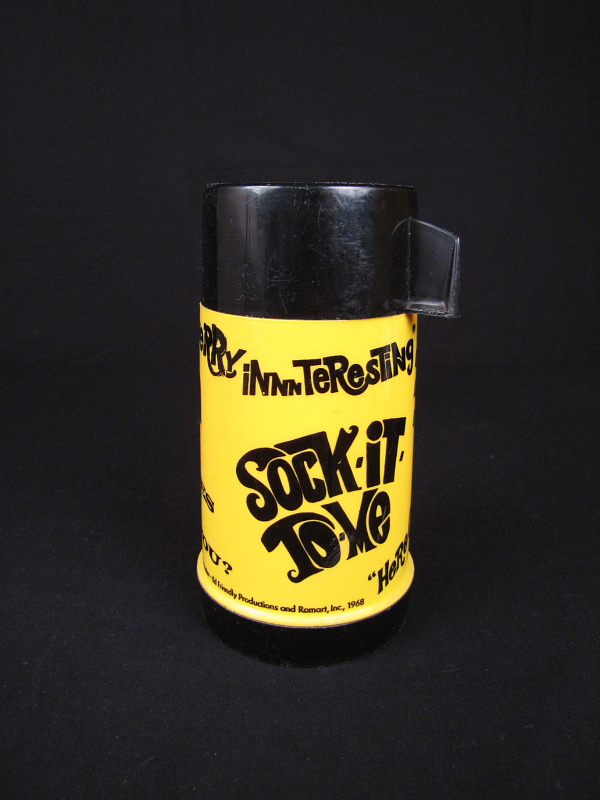

Laugh-In Thermos

Gift of Allan Woodall Jr., 1968. Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History

Laugh-In, a sketch comedy show that ran from 1968 to 1973, was a precursor of late-night TV shows such as Saturday Night Live. This Laugh-In-themed Thermos from 1968 depicts one of the shows catch phrases, “Sock it to me”—and one that some felt helped former President Richard M. Nixon win the presidential election that year when he said it on the show. After that episode, the producer asked Nixon’s opponent Hubert Humphrey to appear on the program and say “Yes, please sock it to me.” Humphrey refused, and later said it may have cost him the election.

Mister Rogers’ Sweater

Mister Rogers’ sweater, 1970s. Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History

In 1968, Fred Rogers walked onto a television set, changed into a sweater and tennis shoes, and sang, “Won’t you be my neighbor?” Rogers created the children’s program Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and hosted it for more than 30 years on PBS until 2001.

An ordained Presbyterian minister, Rogers dedicated his television career to promoting children’s emotional and moral well-being. His show had a friendly conversational style, trips to the Neighborhood of Make-Believe and encouraged young viewers to feel loved, respected and special.

Rogers wore a cardigan sweater on every episode of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, and all were hand-knit by his mother.

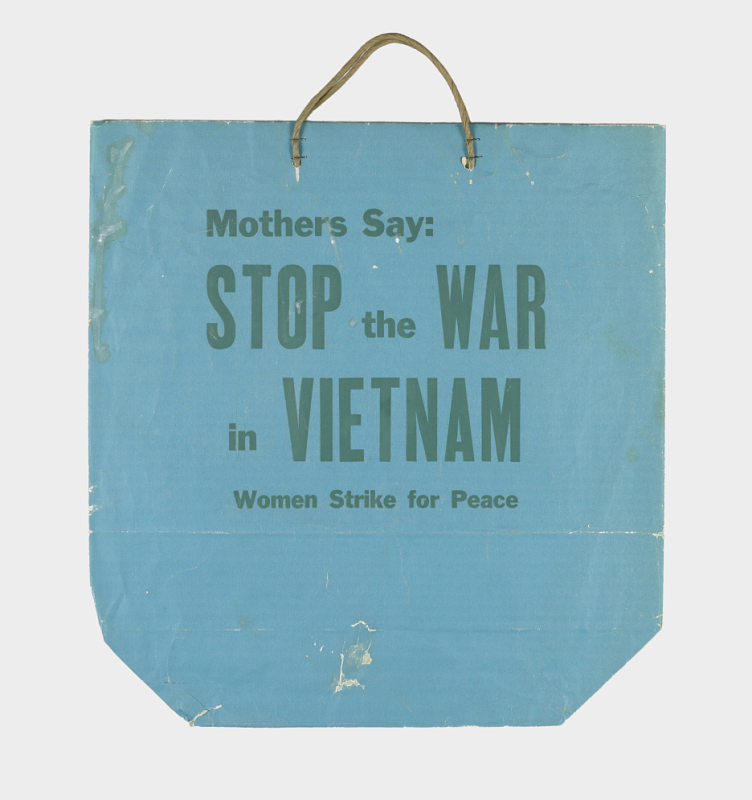

Mothers Say: Stop the War in Vietnam, Women Strike for Peace

Shopping Bag, ‘Mothers Say: Stop the War in Vietnam, Women Strike for Peace,’ 1968;

Offset lithograph on paper, with stapled green raffia handles; 45.1 x 42.9 cm (17 3/4 x 16 7/8 in.).

Gift of Caitlin Fraser James; 1997-17-16; Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

American combat troops had been in Vietnam for three years by 1968 when the North Vietnamese launched a series of surprise attacks known as the Tet Offensive. It caught the U.S.-led forces unaware, and back home in the U.S. it was a turning point in Americans’ support of the war.

This shopping bag is from Women Strike for Peace, an organization created to protest nuclear testing and to demand an end to the war. Founded in 1961 by Bella Abzug, a lawyer, activist and U.S. Representative, and Dagmar Wilson, an activist and children’s book author, the group held demonstrations, petitioned, wrote letters and filed lawsuits. It also used nonviolent, but illegal, strategies such as sit-ins at congressional offices. Much of its activities foreshadowed the anti-Vietnam War movement. Predominantly composed of white middle-class mothers, the group advocated the idea that “average women” could promote peace for the sake of their children.

Olympic Warm-Up Suit Worn by Tommie Smith

Olympic warm-up suit worn by Tommie Smith at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City.

Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture

Standing on the podium at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, American gold-medal winner Tommie Smith, Australian silver medalist Peter Norman and American bronze medalist John Carlos received their medals for the 200-meter race. When the U.S. anthem began to play, the two American athletes raised their fists and kept them raised until the song ended.

All three athletes wore human-rights badges, and Smith and Carlos dressed in such a way to bring attention to various human-rights issues: both wore black socks but no shoes to represent black poverty. Carlos unzipped the jacket of his track suit in solidarity with U.S. blue-collar workers. Both wore beads in protest of those who were lynched and killed.

Smith and Carlos were told to leave the stadium, were suspended from the U.S. Olympic team and received death threats. Their actions remain one of the most significant political protests in Olympics history.

15c Robert F. Kennedy Single

This 15-cent Robert F. Kennedy commemorative stamp was first available Jan. 12, 1979, Washington, D.C.

Copyright United States Postal Service. All rights reserved.

Robert F. Kennedy entered the presidential race late, declaring his candidacy in March 1968 and campaigning on a platform of economic justice and racial equality. After winning the California primary, Kennedy gave his victory speech early June 5 at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. While leaving through the hotel’s kitchen, he was gunned down by Sirhan Sirhan, his head cradled by a kitchen employee as he lay on the floor. Kennedy died the next day. Richard Goodwin, a Kennedy advisor, wrote, “The sixties came to an end in a Los Angeles hospital.”

Memphis' Lorraine Motel

Ernest C. Withers. Restrictions & Rights Copyright Ernest C. Withers Trust. May 2, 2018.

Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture

Martin Luther King Jr. was a Baptist minister and civil rights activist from Atlanta. He organized nonviolent protests for racial and economic equality, and in 13 years he made unprecedented progress. In 1963, he led the massive march on Washington where he demanded change and gave his “I have a dream” speech. King traveled to Memphis in April 1968 to bring attention to a sanitation workers’ strike. All of the workers were black, and they had walked off their jobs in February after two workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, had been crushed to death in a malfunctioning garbage truck; the workers wanted to bring attention to the poor working conditions and low pay. On April 3, with many of the sanitation workers present in the Mason Temple Church, King gave his “Mountaintop” speech: "I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land." In the evening of April 4, as he was leaving Memphis’ Lorraine Motel, King was shot and killed by James Earl Ray. This photo depicts the motel nearly a month after the assassination.

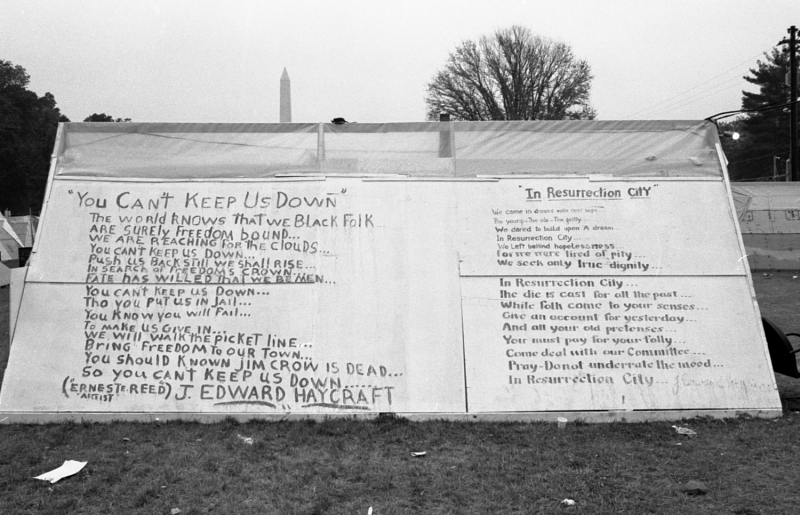

“You Can't Keep Us Down”

“You Can’t Keep Us Down” song lyrics on a tent. Robert and Greta Houston.

Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

In late 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. announced a new march on Washington: The Poor People’s Campaign of 1968, which was to focus on a better economic life for all poor people. It was a three-phase plan: build a temporary town called Resurrection City, which King wanted in Washington so Congress could see it; carry out civil disobedience and protests; and boycott shopping centers and industries to motivate business leaders to pressure Congress to meet the campaign’s demands. The Poor People’s Campaign was intended to be the second part of the civil rights movement, and King wanted it in Washington so Congress and politicians would see it.

King was assassinated before the campaign could begin. But others stepped in to lead the effort. Resurrection City went up on the National Mall and 3,000 people lived in wooden tents for 42 days until their permit expired, and they were evicted June 24 by the National Park Service.

This photo shows the lyrics to two songs written one of the wooden tents at Resurrection City: “You Can’t Keep Us Down” and “In Resurrection City.”

Apollo 8 Pressure Suit

Transferred from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration to Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum 1970

The Apollo 8 mission was launched Dec. 21, 1968. It was the first spaceflight to carry humans in orbit around the moon, take photos of Earth from deep space (including this Earthrise photo) and provide live TV coverage of the moon’s surface. The crew members were Frank F. Borman II, commander of the flight; James A. Lovell Jr., the command module pilot and lunar module pilot William A. Anders.

The astronauts’ Christmas Eve TV broadcast was watched by millions on Earth—it was the most-watched TV show at the time. After orbiting the moon 10 times, the astronauts successfully splashed down in the Pacific Ocean Dec. 27.

This spacesuit pictured above was made for and worn by Anders. The Apollo spacesuits were designed to provide a life-sustaining environment for the astronaut when in space or during unpressurized spacecraft operation.