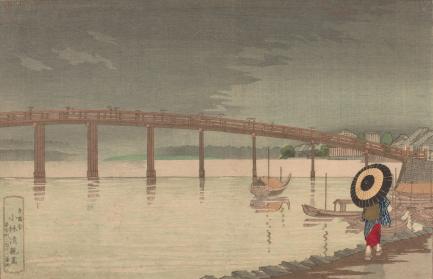

Year-end Market at Sensōji temple

Kobayashi Kiyochika

Meiji era, 1881

Woodblock print; ink and color on paper

H x W (overall): 24.8 x 36.2 cm (9 3/4 x 14 1/4 in)

Robert O. Muller Collection

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian’s “Kiyochika: Master of the Night” Reveals a Lost Tokyo

This release was originally posted Feb. 10, 2014

The Japanese city of Edo ceased to exist Sept. 3, 1868. Renamed Tokyo (“Eastern Capital”) by Japan’s new rulers, the city became the central experiment in a national drive towards modernization. In “Kiyochika: Master of the Night,” on view at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery March 29–July 12, the radically transforming capital city reappears in a series of woodblock prints by Kobayashi Kiyochika. The exhibition will be open during the National Cherry Blossom Festival (March 20–April 22), Washington, D.C.’s springtime celebration of Japanese culture.

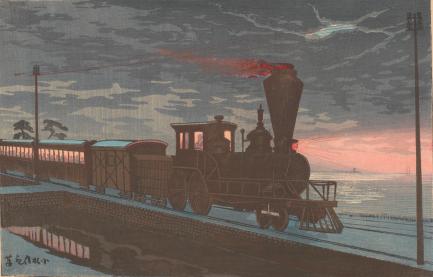

A self-taught artist and minor retainer of the Tokugawa shogun deposed in 1868, Kiyochika (1847–1915) returned to Tokyo from self-imposed exile in 1874 to discover his hometown transformed by railroads, steamships, gaslights and brick buildings—all beyond imagination just a few years earlier. He set out to record these new scenes, where old and new stood together in awkward alliance, in an auspicious and ambitious series of 100 woodblock prints.

While a devastating fire engulfed the city in 1881, effectively ending the project, the 93 prints he had completed were unlike anything previously produced by a Japanese artist. Kiyochika used age-old techniques to produce the prints themselves, but chose unusually subdued colors and mimicked the look and feel of Western photographs, copperplate engraving and oil painting.

“Kiyochika upends the celebratory role of the cityscape in Japanese art and instead creates a nagging sense of unease,” said James Ulak, exhibition curator and senior curator of Japanese art at the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. “His view is a stark one, of men and women on the verge of a world with all the old props kicked away. There are no heavens or hells; no intercessory gods or troublesome demons. Some viewers say they can feel the silence in his prints.”

Widely regarded as Japan’s first artist with a distinctly modern tone, Kiyochika conveyed a sense of curiosity, detachment and melancholy about the vistas and events he depicted. His innovative use of color explored the possibilities of light—both man-made and natural, from dusk to dawn—and subjects drift through moody shades of gray and blue interspersed with fireworks, moonlight, gaslight and fireflies. Equally startling are his human figures. Often silhouetted, they are at once together and alone—observers, rather than actors, in an oddly quiet landscape.

The series was met with some early acclaim, but faded into relative obscurity when Kiyochika abandoned his project after Tokyo’s 1881 fires. He did live to see Nagai Kafu (1879–1959), a prominent critic and literary figure, lead a modest revival of appreciation in the early 20th century. Kafu was a passionate Francophile, and had experienced Paris first hand and later translated the critical works of Charles Baudelaire (1821–67) into Japanese. It was Baudelaire who, upon seeing his Paris transformed, coined the term “modernity” to describe the fleeting, ephemeral experience of life in the metropolis.

Within “Master of the Night,” Kafu’s voice provides an introduction to the artist and his time, but other themes soon take over: Japan’s experimentation with Western technology, the strangeness of Western-style brick buildings, nightlife and the anonymity it provided, and the power of the fire that eventually destroyed the city.

The works on view are part of the Sackler Gallery’s Robert O. Muller Collection, which features among its 4,000 Japanese woodblock prints the most comprehensive survey of Kiyochika’s body of work, including the largest collection of his cityscapes.

The themes of “Master of the Night” echo in the related exhibition “An American in London: Whistler and the Thames” (May 3–Aug. 17), featuring James McNeill Whistler’s (1859–1903) images of London’s iconic waterways. The more than 70 works on view—including paintings, prints, drawings, watercolors and pastels—show the city’s dramatically changing urban environment, and represent a profound assault on the art establishment of the time. In Whistler’s famous nocturnes, the visitor experiences another artist’s impressions of the city at night.

Free public programs include a performance of Western music of Kiyochika’s era by Japanese violinist Mayuko Kamio (March 27; 7:30 p.m.) and “ImaginAsia: Illuminated Nights,” a drop-in workshop where families can create nightscapes of favorite evening activities (March 29 and 30, and April 5, 6, 12 and 13). A film series based on the theme of nocturnes, featuring movies that occur solely at night, will be announced later in the spring.

“Kiyochika: Master of the Night” is made possible by the Anne van Biema Endowment.

The Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, located at 1050 Independence Avenue S.W., and the adjacent Freer Gallery of Art, located at 12th Street and Independence Avenue S.W., are on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Hours are 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. every day (closed Dec. 25), and admission is free. The galleries are located near the Smithsonian Metrorail station on the Blue and Orange lines. For more information about the Freer and Sackler galleries and their exhibitions, programs and other public events, visit www.asia.si.edu. For general Smithsonian information, call (202) 633-1000.

# # #